“Not to be officially reported.”

Henry Hellard was convicted of voluntary manslaughter, and appeals. Reversed.

*482 C. C. Williams, for appellant. N. B. Hays and Loraine Mix, for the Commonwealth.

NUNN, J.

The appellant was tried at the February, 1904, term of the Rockcastle circuit court, on the charge of murder by shooting and killing one Abe Drew. He was convicted of the crime of voluntary manslaughter, and sentenced to a term of 21 years in the penitentiary.

Appellant complains of the action of the lower court in refusing to allow him to prove by J. J. Drew, a cousin of the deceased, that, when he went to Hellard's house after the dead body, he stated to R. M. Johnson and family that, from what Ralph Drew told him immediately after the shooting, Hellard ought to be acquitted; that he (witness) would have done the same thing that Hellard did. The court was right in refusing to allow this statement to go to the jury. It amounted only to an opinion of the witness, and that formed from hearsay, which was clearly incompetent.

The only witness introduced for the commonwealth who professed to have been present at the killing was Ralph Drew, a son of the deceased. He stated that he and his father were walking up the public road which passed appellant's house, and, when about 75 yards from the house, they saw appellant chopping wood on the side of the road, immediately in front of his house; that, when appellant saw them coming, he at once went to his door, and his wife handed him a pistol; that he then took a rest on the fence, and fired two shots at the deceased; that deceased then took from witness a shotgun which he was carrying, cocked it, and fired. Witness thought it went off accidentally. Then the deceased threw the gun down and *483 walked slowly to appellant's gate, picked up the ax, went into appellant's yard after him, with the ax raised in a striking position, and ran him around the house once or twice. Appellant, as he ran, fired two or three shots at deceased, the last one killing him.

Appellant contended that the court erred in adding the following to the instruction on self-defense: “Unless you should further believe from the evidence, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant sought and brought on the difficulty with the deceased in which the shooting occurred in the use or the threatened use of a deadly weapon, or that the defendant and the deceased mutually and willingly entered into a combat with each other with deadly weapons, in either of which later state of case the defendant cannot be excused on the grounds of self-defense.” We are of the opinion that the court did not err in making this addition to this instruction, but did err, to appellant's prejudice, in not also adding “unless you believe from the evidence that he in good faith abandoned the difficulty or mutual combat before he shot Drew.” See Logsdon v. Commonwealth, 40 S. W. 775, 19 Ky. Law Rep. 413. We are of the opinion that, under the proof introduced, it was prejudicial to the substantial rights of appellant not to give him the benefit of this addition to the instruction. According to Ralph Drew's testimony, after the appellant fired the first two shots, his father walked slowly the 75 yards, picked up the ax, and entered appellant's yard, running him around his house, when he fired the last two or three shots. From these facts, and others in the record not necessary to mention, we think the court should have permitted the jury to determine whether or not appellant had, in good faith, given up the intention, if he had such intention, of further attempting to harm the deceased. According to the theory of appellant and his witnesses, he had a clear case of self-defense. But we refrain from further discussing the evidence, or expressing an opinion thereon, for the reason that the case will have to be tried again.

Wherefore the judgment is reversed, and the cause remanded for further proceedings consistent herewith. [8]

---

[May 19, 1904] -

Richard Johnson, who is indicted in the Abe Drew murder case, was over this week looking up witnesses. [9]

---

[May 20, 1904] -

The case, of Henry Hellard who was given 21 years in the pen for the killing of Abe Drew, has been reversed by the Court of Appeals. The Court in rendering its decision, said: "According to the theory of the appellant and his witnesses, he had a clear case of self defense." [10]

The case, of Henry Hellard who was given 21 years in the pen for the killing of Abe Drew, has been reversed by the Court of Appeals. The Court in rendering its decision, said: "According to the theory of the appellant and his witnesses, he had a clear case of self defense." [10]

---

[June 10, 1904] -

Henry Hellard gave bond in the sum of $750.00 and case continued until next court. [11]

---

[September 30, 1904] -

Henry Hellard was given four years in the pen for killing Abe Drew. It will be remembered that at the May term Hellard was given 21 years on this charge, but was granted a new trial by the Court of Appeals. [12]

Henry Hellard was given four years in the pen for killing Abe Drew. It will be remembered that at the May term Hellard was given 21 years on this charge, but was granted a new trial by the Court of Appeals. [12]

---

[January 12, 1905] -

Court of Appeals of Kentucky.

HELLARD

v.

COMMONWEALTH.

January 12, 1905.

PRIOR HISTORY: [***1] APPEAL FROM ROCKCASTLE CIRCUIT COURT--M. L. JARVIS, CIRCUIT JUDGE.

DEFENDANT CONVICTED AND APPEALS. AFFIRMED.

DISPOSITION: Judgment affirmed.

COUNSEL: R. M. JOHNSON AND C. C. WILLIAMS, ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT.

1. We contend that the court erred in not allowing the defendant to prove the character of deceased for peace and quiet or for that of a dangerous man.

2. The court erred in refusing to allow the defendant to ask a witness for the Commonwealth if he had not been impeached three times, and if he had not been convicted three times of moonshining.

3. The court erred in allowing the prosecuting witness to state that one Johnson, just after the difficulty, shot at him (the witness) when there was no evidence that said Johnson had any connection with the difficulty.

4. The court erred in assuming in the instructions that at time of the killing the parties were engaged in a mutual combat, which was not warranted by the evidence, and was prejudicial to the defendant.

AUTHORITIES CITED.

26 Ky. L. Rep. 40; 3 Ore., 74; Blimm v. Com., 7 Bush 329; State v. Sterrett, 68 Ia., 76; State v. Cross, 68 Ia., 180; State v. Lee, 22 Minn. 407; 5 Am. & Eng. Ency. of Law, 873; Roberson's [***2] Ky. Crim. Law & Proc., vol. 1, p. 303; Ky. Digest, vol. 1, p. 30; Payne v. Com., 1 Met., 373; 5 Am. & Eng. Ency. of Law, 580; 99 Ky. 373, 374; 7 Am. & Eng. Ency. of Law, 109; 1 Greenleaf on Ev., 512; 11 Am. & Eng. Ency. of Law, 505; 1 Crim. Defenses, 469; 21 Am. & Eng. Ency. of Law (2d ed.), 248; Feltner v. Com., 23 Ky. L. Rep. 1112; Smaltz v. Com., 3 Bush 33; Cook v. Com., 10 Ky. L. Rep. 202; McClernard v. Com., 11 Ky. L. Rep. 311; Costigan v. Com., 11 Ky. L. Rep. 617; Starr v. Com., 16 Ky. L. Rep. 843.

N. B. HAYS, ATTORNEY GENERAL, AND C. H. MORRIS, ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEES.

1. While the record is not as free from fault as perhaps it should be, in the admission and rejection of testimony, we submit that the court's ruling on the questions presented will be found to be substantially correct, no error having been committed that affects the substantial rights of the appellant.

2. The instructions complained of were correctly given by the court, the evidence showing that the appellant first assaulted deceased by shooting at him twice, and he in fact never abandoned the difficulty in good faith, but ran around the house in order to take shelter for himself behind it, and [***3] to kill the deceased as he did. If, after he first fired the two shots, he in good faith abandoned the difficulty and ran around the house to avoid the deceased, then, although he did first shoot, when pursued to the wall by deceased he had the right to defend himself and the right of self-defense was thereby restored. As to who brought on the difficulty, and as to whether or not, if appellant did bring it on, he thereafter abandoned it in good faith, were facts for the jury to decide from the proof under the law as defined in said instructions. Johnson v. Com., 94 Ky. 78; Lightfoot v. Com., 80 Ky. 516; Oder v. Com., 80 Ky. 32; Terrill v. Com., 13 Bush 256.

JUDGES: JUDGE O'REAR.

OPINION BY: O'REAR

OPINION

[**329] [*447] OPINION OF THE COURT BY JUDGE O'REAR--AFFIRMING.

Appellant appeals from a judgment convicting him of manslaughter. The case, as made out by the prosecution, is that appellant either began an assault on the man he killed, Abe Drew, and prosecuted it up to the fatal shooting, or that he and the deceased mutually and willingly engaged in the affray resulting in the homicide. In either state of case appellant would be guilty of murder or manslaughter, dependent upon the [***4] presence or absence of malice on his part [*448] in engaging in the fight. Appellant's version is that he was assaulted by the decedent, and had to shoot and did shoot his assailant in his necessary self-defense. The conflicting theories were submitted to the jury under appropriate instructions. It was the jury's province--in no sense ours--to pass upon the credibility of the witnesses and the weight to be attached to their testimony. The evidence on behalf of the prosecution is abundant to sustain the verdict. Whether there was any evidence to justify submitting to the jury the question of a mutual and willing affray, it seems to us sufficient to say that there was considerable evidence to the effect that Drew, the man killed, accosted appellant with an insulting remark, and invited him to "come out and take his medicine," meaning that the speaker was prepared to fight, and was challenging appellant to a combat. Appellant, without saying anything, went into his house, got a pistol, and returned, when he and Drew engaged in a shooting match till Drew threw down his gun, when he picked up an ax and continued to fight with it, appellant retreating, and shooting as he went. The evidence [***5] justified the submission of that phase of the case to the jury as was done.

Appellant contends that he abandoned the fight in good faith, even if it be considered that he begun or mutually and willingly engaged in it. That he retreated seems certain. But a retreat is not necessarily an abandonment. It may be only the falling back on a better position, or for strategic reasons, with intention to continue the battle when the advantage warranted it. In such case an assailant who has wrongfully begun a fight can not disarm his adversary of his legal right to pursue his own advantage till his safety is assured. The fight must be abandoned in good faith and in fact. It must be something more than a mere mental determination to quit, even though accompanied with a retrograde [*449] movement. It ought to apprise the other party that his assailant has quit the fight, and has relieved him of the necessity for defense which had been imposed upon him by the assailant's conduct. If this were not so, then one in the wrong, who has put in jeopardy the life of one assaulted by him, and by appearances has produced upon the assaulted a reasonable apprehension of such danger, under which he has [***6] the legal right to fight to the death in his defense, could by his thought change the rightful defense to a criminal act, for changing position alone may not at all indicate that there is to be a cessation of hostilities. The person who has been assaulted, and who under stress of necessity, must act quickly and certainly, ought not to be subjected to the further hazard by his wrongful adversary of having to guess correctly whether a retreating movement is to better the latter's position in the fight or is an abandonment of it. He who creates appearances of necessity for action should bear the burden of relieving the situation of its threatening aspect by appearances equally reasonable in their assurance. The doctrine of self-defense, it [**330] must be remembered, rests both upon actual necessity and apparent necessity. An abandonment of a fight must, therefore, relieve the other party of both actual danger and of such appearance of danger as, operating upon a reasonable mind similarly situated, ought to relieve it of apprehension of immediate or impending danger from that assault. If the person assaulted thereafter renew the conflict, or continue it, then the original assailant's [***7] right of self-defense attaches as if he had not begun it. In this case the instruction merely left to the jury whether appellant had abandoned the fight, if he had begun it mutually and willingly engaged in it. In this it was more favorable [*450] to appellant than he was entitled to, as indicated above.

While testifying for himself appellant was asked whether or not he knew Abe Drew's "character as to peace and quiet." The court sustained an objection to the question. Appellant avowed that his answer would have been that he knew him to be a dangerous man. Appellant was permitted, however, to testify that he was acquainted with Drew's general reputation for peace and violence, and that it was bad. This got before the jury all that was involved in the other question. If Drew was notoriously a dangerous, quarrelsome man, and if appellant knew that fact, all of which was thus placed before the jury, every purpose that could have been served by the excluded evidence had it been admitted is answered. The general rule is that the general reputation only of the party can be inquired into. Had it not appeared by appellant's testimony that Drew was a violent and dangerous man, or had [***8] it appeared on the contrary that he was a peaceable man, it might have been permissible for the accused to show that he personally knew that he was a man of violent passion and temper, and that he always went armed. 1 Roberson's Criminal Law and Pro., 303; Payne v. Commonwealth, 58 Ky. 370, 1 Met. 370.

A number of witnesses testified to appellant's general reputation, tending to impeach him as a witness. Among the number was one John Martin, who was asked on cross-examination: "Is it not a fact that you have been impeached three times in Jackson county?" To impeach an impeaching witness by proof that he has likewise a bad moral reputation, it is not competent to do so in the manner attempted. If one without personal knowledge of the witness' general reputation had undertaken to say that he had heard that he had been impeached in some other proceeding, manifestly the [*451] testimony would be incompetent in form, but not more so than that rejected above. It must be deemed as collateral matter to the issue of the suit on trial.

Appellant was also asked, while testifying as a witness for himself, whether any one had told him or informed him that Drew would kill him. [***9] An objection to the question was sustained. As put, it does not appear but what it was intended to evoke from the witness whether some person had not told appellant, as a matter of opinion or belief, that Drew would kill him; which was clearly irrelevant; that Drew made threats against appellant's life, and that they were communicated to him, were allowed to be proved by appellant and by his informants.

The witness Hubbard did finally testify to the facts which the court refused when he was asked certain leading questions concerning them by appellant, whose witness he was. So, although under the rule that a hostile witness may have leading questions put to him, the question excluded ought to have been allowed, appellant was not prejudiced by the court's ruling.

Whereupon the judgment is affirmed. [13]

---

[September 7, 1906] -

PAYROLED: -- Henry Hellard who was sent to the pen about two years ago to serve a six years' sentence for the killing of Abe Drew was payroled Tuesday and reached here Wednesday. He is looking none the worse because of his confinement. [14]

PAYROLED: -- Henry Hellard who was sent to the pen about two years ago to serve a six years' sentence for the killing of Abe Drew was payroled Tuesday and reached here Wednesday. He is looking none the worse because of his confinement. [14]

-----------

[1] "Farmer Killed in a Fight." Morning Herald, Lexington, KY. February 18, 1903. Page 8. Genealogybank.com

[2] Excerpts from "Locals." Semi-Weekly Interior Journal, Stanford, KY. February 20, 1903. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85052020/1903-02-20/ed-1/seq-3/

[3] Excerpt from "Mt. Vernon." Semi-Weekly Interior Journal, Stanford, KY. February 27, 1903. Page 2. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85052020/1903-02-27/ed-1/seq-2/

[4] Excerpt from "Mt. Vernon." Semi-Weekly Interior Journal, Stanford, KY. March 10, 1903. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85052020/1903-03-10/ed-1/seq-3/

[5] Excerpt from "Circuit Court." Mount Vernon Signal, Mt. Vernon, KY.February 12, 1904. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069561/1904-02-12/ed-1/seq-3/

[6] Excerpt from "Circuit Court." Mount Vernon Signal, Mt. Vernon, KY. February 19, 1904. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069561/1904-02-19/ed-1/seq-3/

[7] Excerpt from "Rockastle County -- Disputanta." The Citizen, Berea, KY. February 25, 1904. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85052076/1904-02-25/ed-1/seq-3/

[8] Hellard v. Commonwealth, 26 Ky.L.Rptr. 38, 80 S.W. 482 (1904). Retrieved from Westlaw.com.

[9] Excerpt from "Rockastle County -- Disputanta." The Citizen, Berea, KY. May 19, 1904. Page 8. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85052076/1904-05-19/ed-1/seq-8/

[10] Excerpt from "Local." Mount Vernon Signal, Mt. Vernon, KY. May 20, 1904. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069561/1904-05-20/ed-1/seq-3/

[11] Excerpt from "Circuit Court." Mount Vernon Signal, Mt. Vernon, KY. June 10, 1904. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069561/1904-06-10/ed-1/seq-3/

[12] Excerpt from "Circuit Court." Mount Vernon Signal, Mt. Vernon, KY. September 30, 1904. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069561/1904-09-30/ed-1/seq-3/

[13] Hellard v. Commonwealth, 119 Ky. 445, 84 S.W. 329 (1905). Retrieved from LexisNexis Academic.

[14] Excerpt from "Local." Mount Vernon Signal, Mt. Vernon, KY. September 7, 1906. Page 3. LOC. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86069561/1906-09-07/ed-1/seq-3/

.

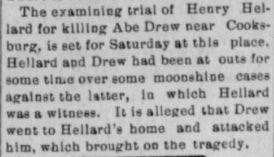

The examining trial of Henry Hellard for killing Abe Drew near Cooksburg, is set for Saturday at this place. Hellard and Drew had been at outs for some time over some moonshine cases against the latter, in which Hellard was a witness. It is alleged that Drew went to Hellard's home and attacked him, which brought on the tragedy. [3]

The examining trial of Henry Hellard for killing Abe Drew near Cooksburg, is set for Saturday at this place. Hellard and Drew had been at outs for some time over some moonshine cases against the latter, in which Hellard was a witness. It is alleged that Drew went to Hellard's home and attacked him, which brought on the tragedy. [3] Henry Hellard had an examining trial here Friday and his ball fixed at $500 on charge of killing Abe Drew near Big Hill. [4]

Henry Hellard had an examining trial here Friday and his ball fixed at $500 on charge of killing Abe Drew near Big Hill. [4] The case against Henry Hellard for the killing of Drew, was called Tuesday, when both sides announced ready and the following jury was selected to try the case: J. S. Langford, Geo. Ketron, Jack Burke, George Parsons, Thomas Taylor Jr., Thos. Taylor Sr., W. D. Mullins, W. D. Levisay, Thos. Mink, J. D. Hamm, John Cummins, and Geo. Proctor.

The case against Henry Hellard for the killing of Drew, was called Tuesday, when both sides announced ready and the following jury was selected to try the case: J. S. Langford, Geo. Ketron, Jack Burke, George Parsons, Thomas Taylor Jr., Thos. Taylor Sr., W. D. Mullins, W. D. Levisay, Thos. Mink, J. D. Hamm, John Cummins, and Geo. Proctor.

The case, of Henry Hellard who was given 21 years in the pen for the killing of Abe Drew, has been reversed by the Court of Appeals. The Court in rendering its decision, said: "According to the theory of the appellant and his witnesses, he had a clear case of self defense." [10]

The case, of Henry Hellard who was given 21 years in the pen for the killing of Abe Drew, has been reversed by the Court of Appeals. The Court in rendering its decision, said: "According to the theory of the appellant and his witnesses, he had a clear case of self defense." [10]

Henry Hellard was given four years in the pen for killing Abe Drew. It will be remembered that at the May term Hellard was given 21 years on this charge, but was granted a new trial by the Court of Appeals. [12]

Henry Hellard was given four years in the pen for killing Abe Drew. It will be remembered that at the May term Hellard was given 21 years on this charge, but was granted a new trial by the Court of Appeals. [12] PAYROLED: -- Henry Hellard who was sent to the pen about two years ago to serve a six years' sentence for the killing of Abe Drew was payroled Tuesday and reached here Wednesday. He is looking none the worse because of his confinement. [14]

PAYROLED: -- Henry Hellard who was sent to the pen about two years ago to serve a six years' sentence for the killing of Abe Drew was payroled Tuesday and reached here Wednesday. He is looking none the worse because of his confinement. [14]

No comments:

Post a Comment